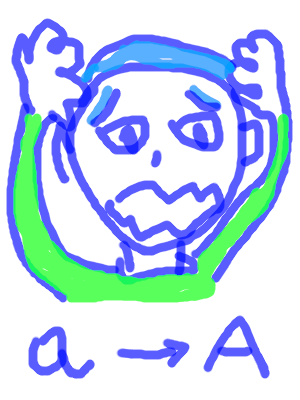

As a joke, a work colleague—who had known me only briefly—asked another colleague in my presence, who had known me much longer, to name one of my strengths and one of my flaws. The flaw came to mind immediately: I'm resistant to change. For the strength, he had to think for a few seconds, then said that I always adapt. Thus provoking hearty laughter from those present.

As happens with those episodes whose significance, both emotional and symbolic, is almost overlooked in the moment, after a few days that apparent contradiction about me came back to mind. It lit a bulb and prompted me to formulate a reflection—certainly not definitive—on the theme of change in a corporate context and on a subtle misconception that, from time to time, one stumbles upon: believing that resistance to change is one of the possible characteristic traits of a worker.

I immediately exclude from my reasoning the extreme cases: those individuals, more unique than rare, so intolerant of change that they wouldn't even replace a toothbrush worn down to the implausible. These people represent pathological cases and, as such, should be treated by mental health professionals.

I also exclude the possibility of judgment based on the first reactions that follow news of the change, because they are never indicative or definitive. There are those who immediately show enthusiasm—often fueled by great expectations—only to change their minds later; those who show indifference but later understand they've underestimated the scope of the novelty; those who display forced serenity so as not to disturb themselves and other colleagues and to have time to develop a more solid idea; those who appear serene because, in bad faith, they've immediately intuited that they can exploit the circumstance for their own advantage—naturally at the expense of the company or other colleagues. There are also those who openly express perplexity, as honest and transparent people do, or those who complain like contrarians: both categories are mostly harmless, who deep down only hope that someone will help them change their minds, because they don't want to feel bad.

All this to say that, although the category of those "easily disappointed" is the most frowned upon, I don't believe at all that this attitude is correlated with the real ability to face change.

That said, I venture the thesis that there are no workers truly resistant to change: they can only seem so or, in the worst cases, become so—even temporarily—due to the way their superiors, if inadequate for the role, manage the change itself. These latter, in my opinion, are the only category of workers incapable of dealing with change.

Before arguing my thesis, I want to clear the field of a type of change that allows those in charge to put, with hasty ease, their hands up front: exogenous changes. Those, that is, that come from outside the company and are dictated, for the most part, by natural events, by supra-company entities (such as trade associations), or by political or judicial bodies. In these cases, it is said, "there's nothing to be done." But is that really so? Really, for example, does the legislator always indicate in great detail not only what to do differently than before, but also how to do it?

Let's say a law requires a new form to be filled out in the face of a certain circumstance. One might think there's not much else to do but resign oneself to following the instructions and filling it out. If the worker has reluctance, therefore, they should blame the politicians they voted for.

Well, it's not exactly like that. Often there are many ways to fill out a form. One of the worst is to do it manually, alternating it with other activities and without checking the final content. One of the best is to do it digitally, with adequate software that automatically acquires—from the relevant databases—the entire content to be entered, then filling out all the forms assembly-line style. This way, errors are minimized and, consequently, the need for checks (which can be limited to sporadic samples).

Even in this case, however, the excuses and clichés are not lacking: "the perfect is the enemy of the good," "we don't have the resources to create this system, let's do everything by hand for now," and so on. But who said we must immediately achieve the optimum? Better to stop for a moment, think, organize based on available resources and, together with the team, identify the most suitable middle ground as a starting point. Then plan subsequent improvements.

I invite the reader to find any counterexample that disproves me. They won't find any, for a logical reason: even in the face of absolute constraints, there always remains at least a margin of choice—in time, in manner, or in the meaning of the response to change—because this goes hand in hand with the possibilities and abilities of human beings themselves. If one day human beings no longer have multiple abilities and possibilities but only singular ones, they will probably just become extinct.

Having eliminated even the most simplistic justifications, we arrive at the real problems related to change. These, in general, occur when poor decisions are made at the top floors of the company and/or when there's a total disconnect with the operational levels and/or inertia of managers at any hierarchical level and/or general lack of transparency.

Suppose the top management makes a decision that results in a change. It happens that such decisions don't always appear to be the best possible to those who suffer them. In these cases, there are various ways to prevent resistance to change: the top management can argue extensively and in a structured way the motivations, revealing as many behind-the-scenes details as possible (within the limits of confidential information). Thus, when a seemingly absurd or unjustifiable decision turns out to actually be good or excellent, the lower layers of the hierarchy can become convinced and willingly collaborate.

If instead the decision was objectively wrong, being clear and transparent won't be enough to obtain the moral support of the lower floors. Here the strategic role of intermediate hierarchical managers comes into play, who can at least partly remedy the wrong decision. First, they should, with intellectual honesty and always with due respect, admit that the top floors might have made a mistake. Then, while reminding that the decision must still be accepted, they should analyze the situation together with their collaborators to understand what margins exist in managing the change and how to optimize its impact. Finally, they should take charge of the proposals—their own and their collaborators'—and direct them to the top management, with the right manner and timing, so that the course can be corrected, in whole or in part, for the good of the company.

If this process is not implemented at least in part, it's easy for a worker to appear resistant to change, even though in most cases, shortly after, they adapt diligently (or, where possible, change companies). At the basis of all this reasoning is always teamwork and the active and proactive participation of everyone, within their own role.

Managers must manage "reluctance" even in the post-change period. It can happen that a change is immediately welcomed favorably at every level, or with apparent indifference, for prudent wait-and-see. And it's not at all certain that, at a later time—once the change is fully realized—intolerance and opposition won't emerge.

Even in this case, intervention is necessary, although sometimes it's more difficult: when only a small group, or even a single person, hasn't digested a change that continues to seem positive to everyone, there's a strong temptation to react with indifference or to isolate the subject, rejecting what they would have to say. There are two possibilities. If the objections are valid, even only in part, ignoring them is a missed opportunity: it's simple to avoid the fatigue of managing a problem that wasn't noticed before and that only one person has detected, easily silenced, unlike the masses. But it's not certain that, sooner or later, others won't start noticing the problem too. Therefore, never miss the opportunity to take corrective action if someone senses, even after the fact, that something is wrong.

The second case is when the objections are unfounded. At that point, one simply needs to listen carefully to whoever expresses discomfort: help them resolve doubts and perplexities, give them tools for better understanding and more effective operation—in short, put them in a position to face the change that, unlike others, has put them in difficulty. If the support action doesn't work, one must ask whether one hasn't been able to help them—and, in that case, seek help to do it better—or whether the change has touched that person's objective limits. In this latter case, it may be appropriate to propose a different task to them, one that values their other abilities.

In conclusion, excluding pathological cases, resistance to change is never a worker's attitude, but a signal whose emergence must be prevented as much as possible and, if it manifests, managed in the best way. Also because it sometimes represents an opportunity that's even salvific. All of this, almost always, at the cost of only a minimum effort of goodwill on the part of those called upon to lead.